Athens

ABOUT THE ROUTE

ABOUT THE ROUTE

From Cincinnati, Chillicothe, Columbus, or Newark, there are several routes into southeastern Ohio, leading to Athens or Marietta. Most are quite scenic; many are a bit slow-going, offering plenty of time to take in the sights along the way. The many natural beauties and tourist amenities of the “Hocking Hills” region, centered on the historic towns of Logan and Nelsonville, are highly recommended; we feature here in particular the Leo Petroglyphs, Buckeye Furnace, and Zaleski Mound.

The Visitors Center of the Wayne National Forest presents many resources for understanding and exploring the ecology and history of southeast Ohio.

LEO PETROGLYPHS

LEO PETROGLYPHS

Leave Chillicothe via US 35 through the villages of Richmond Dale and Savageville, then turn left for about 4 miles to the village of Leo. The road to the site (signposted) heads northwest for about a half-mile. On an exposed dome of sandstone, surrounded by a walkway, the centuries-old petroglyphs (rock-writings) are inscribed. There are 37 figures of birds, fish, feet, hands, and human and composite creatures, visible as the diffused daylight washes across the surface. Their subtlety is revealed, as one visitor has suggested, by staring for a few moments until they begin to show, like the stars at night.

Most likely they had a meaning when taken together, rather than being hieroglyphs standing for individual words. Archaeologist Brad Lepper:

I think there’s a story there to be read, but the key, we don’t have the key anymore, so I don’t think we can read it now. But there are elements like the human face with the antlers, I think in many rock art traditions in America, that seems to reflect spiritual power. So it may not be a photographic representation of a creature with antlers, but it may just represent a Shaman, a Medicine Man or Woman, and the antlers are an indication of the spiritual power that that person had. So there are aspects of it that I think we can tease out, but… I think the meaning of the entirety of it is lost to us.

From the weathering of the rock and the nature of the symbols, experts think the petroglyphs are less than a thousand years old, probably done in the “Fort Ancient” era, or by historic Indians. Living among these hills, probably in villages, they would have been drawn to the nearby Scioto Salt Licks in Jackson, and the Zaleski Flint deposits to the north in what is now Vinton County.

At one point recently the recessed lines were traced in dark material to make them more visible, though that is mostly faded now. The park is called the Leo Petroglyphs State Memorial, and the inscribed outcrop stands at the edge of a beautiful ravine. Trails explore both in and around the 60-foot sandstone cliffs. There is a small bridge, and abundant birds and wildflowers.

In 1780, the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger observed that the Indians along the Muskingum River often recorded their stories with paint on forest trees. He wrote:

If a party of Indians have spent a night in the woods, it may be easily known... by their marks on the trees, to what tribe they belong. For they always leave a mark behind made either with red pigment or charcoal. Such marks are understood by the Indians who know how to read their meaning. Some markings point out the places where a company of Indians have been hunting, showing the number of nights they spent there, the number of deer, bears and other game killed during the hunt. The warriors sometimes paint their own deeds and adventures, the number of prisoners or scalps taken, the number of troops they commanded and how many fell in battle... These drawings in red by the warriors may be legible for fifty years…

The Leo Petroglyphs are the closest thing we have indicating how such inscriptions may have been part of a visual language with specific meanings, although those meanings now elude us.

A timber structure built by the WPA in the 1930’s shelters both a picnic area and the petroglyphs.

The human face with antlers probably represents a leader with spiritual powers.

BUCKEYE FURNACE

BUCKEYE FURNACE

Buckeye Furnace State Memorial, is a beautifully reconstructed charcoal-fired blast furnace typical of those serving Ohio’s Hanging Rock Iron Region from the mid-1800s. Leave Leo to the southeast, through the villages of Coalton and Glen Roy. At Wellston, take SR 327 south, across SR 32, to make a left turn onto SR 124 at Berlin Crossroads. At 3.8 miles, go right on Buckeye Furnace Road; the site is well signposted. (123 Buckeye Park Road, Wellston, OH 45692, 740-384-3537).

The approach road passes through watery lowlands surrounded by forested hills. Soon the massive, reconstructed, stone blast furnace complex appears beside the road. Through the open-air casting shed, the mouth of the charcoal-fired oven is visible. To the left is the engine house, where steam heat from the furnace would drive air compressors to increase the heat of the fire. A timber superstructure above the chimney, reachable by a separate trail, is the charging shed where the ingredients (iron ore, limestone) were measured in from above. Nearby atop the bluff is also the huge, open-air storage shed, for the vast quantities of materials needed to keep the furnace running continuously. Visitors can see the casting shed, charging loft, and steam-engine house, as well as the company store serving as an orientation area.

The Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio prospered during and just after the Civil War, as many small company towns of 300-400 residents operated the furnaces, and produced the iron for America’s early industry. All the key raw ingredients were locally plentiful: wood for fires, limestone for flux, and the iron ore itself. Vast tracts of forest were depleted in the process, and families were conscripted in servitude in these isolated, self-contained communities, which were structured around their own schools, churches, and even commerce and currencies wholly controlled by the “Company Store.” A restored company store and ironmaster’s house, as well as a covered bridge, are visible at Buckeye Furnace.

To reach Athens, return to SR 32 at Berlin Crossroads and head northeast.

The restored iron-smelting complex at Buckeye Furnace illustrates mid-19th century industrial techniques.

The Buckeye Furnace charging shed, with its giant scoop, was used to feed the smelting fires from above.

ZALESKI MOUND

ZALESKI MOUND

Another route between Chillicothe and Athens (US 50) passes through the picturesque small town of McArthur, the seat of Vinton County (historic buildings, cafés). Go north out of McArthur and then head east on a county road, across a high, treeless ridge with long views of farmland and forested hills, to the tiny, remote village of Zaleski.

On the edge of the village, on the grounds of a State Forest Headquarters, stands one of Ohio’s most beautiful mounds. Its elegant profile is gracefully ringed by a gravel path and a circle of young trees; adjacent is a small memorial to veterans.

While in the Zaleski area, inquire about the Moonville Tunnel (a bit northeast from the village), built for a now-abandoned nineteenth-century railroad line. It is one of many in the region, but is now unique both for its accessibility and the appeal of its associated local legends.

To reach Athens, return to US-50 and head east via Albany.

Zaleski Mound

THE HOCKING HILLS REGION

THE HOCKING HILLS REGION

The main route into southeastern Ohio from Columbus or Lancaster (US 33) passes through the Hocking Hills tourism region. Logan is the main headquarters for exploring among the many scenic and recreational opportunities of the greater Hocking River valley. Nine state parks encompass a variety of natural wonders including large overhanging cliffs and waterfalls, caves, and nature preserves.

A bit farther south along US-33 is Nelsonville, whose well-preserved town square is the setting for many festival and arts events. The nearby train station is headquarters for the Hocking Valley Scenic Railroad, run by volunteer railroaders and a main attraction of the county. Hocking College nearby operates Robbins Crossing, a collected village of 1850s log cabins that gives the flavor of 19th Century life in the region.

Along US-33 between Nelsonville and Athens is the headquarters of the Wayne National Forest, an excellent resource for learning about the history and ecology of the region, and for getting oriented to miles of hiking trails throughout the region. The Forest is divided between Athens and Marietta sections, and superb maps are available at the Visitors Center.

Ash Cave is one of the more beautiful of several natural wonders in the Hocking Hills region.

ATHENS AND OHIO UNIVERSITY

ATHENS AND OHIO UNIVERSITY

The New Englanders who came to settle southeast Ohio in 1788 believed in education. Their Ohio Company of Associates (see Marietta itinerary) set aside two whole townships for the “American Western University,” which was to be modeled on the ones back home: Yale and Harvard. It was the first college west of the Alleghenies, and in 1804, the year after statehood, the new Ohio legislature renamed it “Ohio University.”

Though far from the Ohio River, the site was fed by the Hocking River, which promised easy transportation to the Ohio. Reflecting their high ideals, the founders named their university town “Athens” after the Greek birthplace of Western Civilization.

From near the “roundabout” down by the Hocking River, take Dairy Lane to reach The Ridges and the Dairy Barn, two of Athens’ outstanding arts venues. At the sharp bend, turn right and up the hill to explore The Ridges, fascinating remnants of a huge, nineteenth-century asylum, with sprawling and ominous Victorian buildings now largely converted into university uses and the Kennedy Museum of Art, with a stunning collection of weaving and jewelry by Southwest Indians. Edwin and Ruth Kennedy collected both historic and contemporary examples, beginning in the nineteen-fifties, and it is possible to trace a continuity of themes and techniques.

The Dairy Barn Art Center, 8000 Dairy Lane, is home to the most significant art quilt show in the nation: the National, held every two years. (The town of Athens has long been known as a hub for craftspeople, with galleries and pottery showcases scattered through the uptown area, and in nearby Nelsonville.) From the Dairy Barn, a walking path leads to Athens’ (and the old asylum’s) historic cemeteries.

Athens originated the “quilt barn” idea, based on the old quilting art: owners paint a quilt square on their barn, about 8’X8’. There are several barn quilt trails (car or bicycle) in the area; inquire locally.

Several of Ohio University’s earliest buildings survive, around the campus green, including Cutler Hall, erected in 1816

The Dairy Barn hosts the famous Quilt National competition, in odd-numbered years, featuring art quilts on display all summer.

THE PLAINS

THE PLAINS

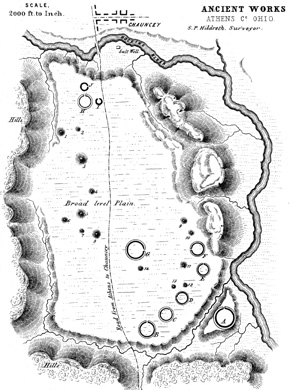

The Plains is a village immediately to the northwest of Athens containing the remnants of the Wolfes Plains Mounds and Earthworks, a major Adena era complex. Reach The Plains via SR-33, or hike or bike there on the Hocking Adena Bike Trail, which also extends northward all the way to Nelsonville.

The Plains occupies an unusual, flat platform above the Hocking River, among abruptly-rising hills. Once called “Wolfes Plains,” this distinctive land-form has been, since about 300 BC, a spectacular sacred place. Squier and Davis recorded as many as 30 earthen circles and mounds, covering the terrace. There is no evidence of ancient dwelling sites, suggesting the people lived in the surrounding hills (where there are more mounds), and descended to the plain for ceremonies and rituals among these earthen forms.

Today, two large mounds remain to be seen in the town, named Hartman and Woodruff-Connett. More low mounds and circles can be detected in the area, though barely, in fields, or beneath buildings. The old Indian trail that bisected the terrace has become SR 682, around which the town clusters.

HARTMAN AND WOODRUFF-CONNETT MOUNDS

HARTMAN AND WOODRUFF-CONNETT MOUNDS

The largest of the remaining mounds in The Plains, the Hartman Mound, stands 40 feet high, and 140 feet in diameter. Going north on SR 682, turn left on Mound Street (confirm this) for about one quarter mile.

It has never been excavated, although probably contains graves similar to the one found, during the nineteenth century, in a smaller mound nearby: there, a log tomb held the deceased, surrounded by five-hundred rolled copper beads, and a tubular pipe.

Although there is an implied pathway, climbing is not encouraged, out of respect for both the ancient graves and the private landowner.

Follow Mound Street or the Adena Drive loop to reach the smaller, nearby Woodruff-Connett Mound, the largest of what was once a cluster of three. It stands 15 feet high, with a base diameter of 90 feet, and is now mostly tree-covered. Along part of the base you can see a slightly elevated “apron” of earth, which may belong to the ancient design. The mound sits on land preserved as open space by the Athens County Historical Society and Museum. Look for a slight swell in the grass nearby, where a second mound once stood, about half the size of this one.

Ongoing research reveals that the people who built the great circles and mounds of The Plains lived along the terraces of the surrounding hills. They also built small mounds on the peaks of the hills using earth and stone. When they descended to the sacred plain below, their purpose seemed to be to join with others in building and using the large earthworks – gatherings that probably combined commercial, civic, social, funerary, and spiritual importance.

Dr. Elliot Abrams, an archaeologist at Ohio University, studied the Armitage Mound nearby as it was being destroyed for a housing project in 1987. He found a central burial of a man in his 50’s, surrounded by 14 cremated burials – perhaps a sign of social hierarchy. About 40 small shallow fire pits at various levels suggested people revisited the mound at intervals, burning substances and adding soil to the mound over perhaps four to six generations. This suggested to Abrams an association of families or groups living in the hills around The Plains, who gathered to honor the central figure, bringing their already-cremated ancestors together here. Bladelets in the fill show that these people had connections with the Middle Woodland (Hopewell) tradition, although in this valley the earlier Adena era practices continued to dominate.

Play video

Play video

The Plains offers a prime example of the earth-building and settlement traditions that archaeologists call “Adena” (Squier and Davis).