Tarlton Cross

ABOUT THE ROUTE

ABOUT THE ROUTE

The diagonal route between Chillicothe and Newark approximates the possible “Great Hopewell Road,” an ancient route suggested by recorded remains near its northern end. About midway is the Tarlton Cross Mound, in the village of the same name, a unique plus-sign-shaped mound crowning a small wooded ridge at the end of a scenic trail. Nearby Circleville was planned with concentric streets inside a huge ancient, earthen ring (originally with an adjoining square). The road northward through Lancaster skirts the scenic Appalachian Plateau; at Buckeye Lake (lined with limestone slabs from a huge stone mound) are the remains of an early 20th century amusement park and resort village.

The Ohio A portion of the Ohio and Erie Canal is preserved southwest of Circleville.

OHIO AND ERIE CANAL

OHIO AND ERIE CANAL

Leave Chillicothe going north on State Route 104. About 12 miles above Mound City, turn right in the village of Westfall onto Canal Road, which parallels beautiful remnants of the old canal and towpath.

This route, and Canal Park outside Circleville, showcase some of the best remains of early Ohio’s ambitious canal system. This is a piece of the Ohio and Erie Canal, one of two systems created in the 1830’s to carry goods between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River. The canals were a huge undertaking, built largely by poor Irish laborers. The cost nearly bankrupted the state, but as the backers had hoped, they could carry products from Ohio’s farms, mills, and mines to eastern markets much more easily than wagons, and at one-fifth the cost.

Because both the canals and the ancient earthworks were built near Ohio’s rivers, they can often be found near each other. The Ohio and Erie, for example, is evident near Newark, and in Chillicothe. The canals gradually lost out to the railroads, and closed for good in 1913. In aptly-named towns like “Lockington” and “Lockbourne,” we can still see remnants of the canals: great stone hulks of elaborate locks, gates, and channels. But here, between Circleville and the village of Westfall, is a rare section with both waterway and tow-path intact.

Play video

The remnants of massive stone canal locks are found along the former routes, often buried in the woods as here near Baltimore, Ohio.

CIRCLEVILLE

CIRCLEVILLE

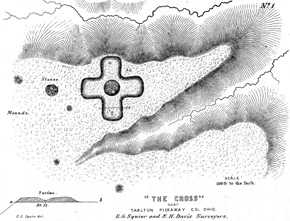

Turn east onto US 22 and cross the river into downtown Circleville, where the road becomes Main Street, the axis line that bisected the ancient earthworks here, a giant circle (from which the town took its name) and an attached square. Circleville was the home of Caleb Atwater, postmaster and eccentric surveyor of Ohio antiquities in the 1820s.

Circleville was laid out in 1810, carefully designed within its 22 acre, double-walled, ancient earthen ring. In building their central octagonal courthouse, the townspeople destroyed the original central burial mound and semi-circular pavement; but the founders had preservation ideals, like their predecessors in Marietta, and envisioned a novel blend of ancient and modern.

Within 20 years, though, complaints arose. The yard around the courthouse attracted swine. The circular plan of the streets was inefficient, especially in view of added business coming to town via the Ohio and Erie Canal.

By 1837, the complainers had won: the state-chartered “Circleville Squaring Company” began the job of destroying the unique town plan, though it took 15 years because of protests. Today only the central axis survives, as Main Street.

Circleville feels like the center of Ohio every October, when throngs of visitors arrive for the annual Pumpkin Festival. Two county historical museums, both in historic houses, help tell the region’s history. The Clarke-May House (162 West Union Street, open April to October, Tuesdays to Fridays from 1:00 to 4:00 p.m.) is stuffed with materials from every historical period. Go upstairs to see the model of the Circleville Earthworks executed by a local dentist using dental plaster. Nearby in the Moore House (304 South Court Street), the Genealogical Library also has historical displays; ask to see the original colored drawings of the circular Circleville made by confectioner George Wittich.

Though Circleville’s original octagonal courthouse is gone, today’s local citizens (the “Roundtown Conservancy”) have preserved an excellent example of a private octagonal house, the Gregg-Cites House of 1856, which they moved in 2004 from a Walmart building site to a safe location on Cites Road, off South Court Street.

Play video

Squier and Davis showed the double ring and adjoining square at Circleville, its long axis later became Main Street.

THE PICKAWAY PLAINS AND LOGAN ELM

THE PICKAWAY PLAINS AND LOGAN ELM

An excursion south of Circleville along US 23 leads to a group of distinctive rolling hills of great fertility, which once formed a natural open prairie several miles across. In the 1600s, people from the Shawnee and other tribes, driven westward by settlement, began to establish villages and farms here. Despite early decrees that no settlers could live west of the Appalachians, new colonists kept arriving and clashing with the Indians. It was at a peace conference here that the Shawnee agreed to give up their lands east and south of the Ohio River – the first concession of land by Indians actually living in the Ohio country.

A small, tranquil park (five miles south of Circleville and one mile east of US 23 on SR 361) honors Chief Logan, and his world-famous speech on Indian / White relations. Logan was born a Cayuga in Pennsylvania, where he grew up with many white friends. In 1770, he married a Shawnee woman and moved to the Ohio Country, to live among the Mingo – a group originally from Iroquois roots, like himself. He urged peace with settlers until some of them attacked his village, killing his mother and sister.

Then Logan led the Mingo on raids of revenge against the whites, prompting Lord Dunmore of Virginia to bring an army westward against the Indians. After a battle at Point Pleasant (in today’s West Virginia), the other Indian leaders finally sued for peace, in 1775.

That peace council was held here, on the vast and fertile “Pickaway Plains.” Logan refused to attend, but sent a speech to be read, expressing his feelings of betrayal and despair. His eloquent words were spoken under a great elm tree here:

I appeal to any white man to say that he ever entered Logan’s cabin, but I gave him meat; that he ever came naked, but I clothed him... He will not turn his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? No one.

The great elm survived until the 1960s, when it was replaced.

Play video

The distinctive rolling prairie lands of the Pickaway Plains remain one of Ohio’s richest agricultural regions.

The words of “Logan’s Lament” are inscribed on a monument near the newly-replanted “Logan Elm” tree.

TARLTON CROSS

TARLTON CROSS

Leave downtown Circleville by SR 56, heading southeast, and in 9 miles go left on SR 159 for 4 miles into the village of Tarlton. Turn left immediately onto Reading Road for about ¾ mile to a shaded parking area on the left.

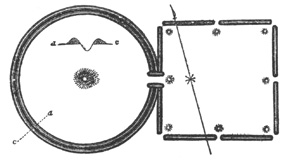

In this Fairfield County Park, the Cross Mound is reached by a picturesque CCC-era concrete suspension bridge and pathway. The mound is shaped like a 90-foot plus-sign. A depression in its center may be original to the design, or an early modern intrusion. Archaeological explorations have not yielded any artifacts, or any definitive evidence of the date and cultural origins of the figure. The site is a narrow, slightly sloping ridge, and the Cross seems to have been shaped in a most unusual way: by the subtraction as well as the addition of soil. Dr. Brad Lepper explains:

It’s not simply a built up cross. The shape of the cross is partly determined by excavating the ground, the down slope part, and then taking that earth and piling it up to make the upslope part of the cross. So down slope when you do a soil profile, there is nothing; the mound isn’t constructed at all. The outer part of it was excavated away to define the cross. The upper part was built up.

Just to the southwest of the cross stand four earthen mounds, now obscured among the trees. The mounds have recently been discovered to form a perfect square, 260 feet on its diagonals – one quarter of the hypothetical “Hopewell Unit of Measure.”

Squier and Davis illustrated the Cross Mound in 1848, showing some of the out-lying mounds later discovered to be in a perfect square.

LANCASTER

LANCASTER

Continue north on Reading Road (which changes its name in the next county) for about two miles, then go right to meet northbound SR 156 towards Lancaster. SR 156 joins US 22 before heading into Lancaster, a historic town and the seat of Fairfield County. About halfway between the US 33 bypass and downtown, watch for Stonewall Cemetery Road on the right. A mile south stands one of Ohio’s most remarkable octagonal structures: an early 1800s private cemetery, where a handful of graves are surrounded by an exquisitely crafted, eight-sided, sandstone wall. The huge blocks are perfectly fitted. In the center grows a Lebanese Cedar tree (inquire locally for access).

The city of Lancaster has a pleasant downtown district with many shops, several important museums and historic houses, and very impressive public buildings. The city was one of the Zane’s Trace settlements and like Somerset was laid out in the distinctive Pennsylvania manner: the town square is formed by leaving open the corners of four adjacent city blocks.

Downtown Lancaster has an unusually rich collection of fine museums, all within easy walking distance of each other and the square: the Georgian Museum (a spectacular, period-furnished mansion at 105 East Wheeling Street, 740-654-9923), the Decorative Arts Center of Central Ohio (an impressive arts museum in the historic Reese-Peters House, 145 East Main Street, 740-681-1423), the Sherman House Museum (home of the Sherman Family and their famous Civil War General son, William Tecumseh, 137 East Main Street, 740-687-5891), and the Ohio Glass Museum (with a glass-blowing studio, at 124 West Main Street, 740-687-0101).

The surrounding country roads in Fairfield County lead to many golf courses, historical and scenic parks, and covered bridges. Take SR 37 north out of Lancaster towards Granville. This route skirts the edge of the Appalachian Plateau, and also approximates the route of the possible “Great Hopewell Road,” an arrow-straight, sixty-mile ancient thoroughfare which may have connected Newark and Chillicothe, the Hopewell era’s two greatest ceremonial centers (see Newark). Tantalizing evidence discovered on old aerial photographs and drawings by Dr. Bradley Lepper of the Ohio Historical Society, has yet to be proven by on-the-ground surveys.

Stonewall Cemetery just outside Lancaster is one of Ohio’s most unusual, and beautifully crafted, octagonal structures.

The Decorative Arts Center, one of several grand mansions recalling Lancaster’s early wealth, is also a fine museum.

BUCKEYE LAKE

BUCKEYE LAKE

About 10 miles above Lancaster (just after Bickel Church Road) turn right on Deep Cut Road, angling northeast along the former canal bed toward Millersport. Just when the road climbs a small hill, one of early Ohio’s most impressive engineering feats comes into view: the Deep Cut, a 2-mile-long, straight, 60-foot-deep channel created to bring the canal out of its source at nearby Buckeye Lake. After Millersport, follow the small roads through the oddly picturesque old resort villages along the northern embankment of the lake.

The long history of Buckeye Lake dates back to the construction of this reservoir in the early 1800s as a feeder for the state’s new canal system. The lake was lined partially with huge limestone slabs from a nearby mound. By 1900, the canals had been long abandoned, but there were lively amusement parks along the shore. There is now a state park, where a historical museum tells the stories, and boat tours of the Cranberry Bogs are available (inquire locally).

Return to SR 37 to head north into Granville, or continue via SR 79 into Heath and Newark.

The new, the old, and the odd characterize the settlements along the constructed northern embankment of Buckeye Lake, the headwaters of southern Ohio’s canals.