Mound City

ABOUT THE SITE

ABOUT THE SITE

Excursions among the monumental antiquities of south central Ohio should begin at Mound City, and the Visitors Center at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, with its fine artifact collection and orientation programs.

To reach Mound City, take Chillicothe’s Main Street two blocks west of Paint Street, then go north on State Route 104 for 3 miles. After passing between two large prisons, enter the Park headquarters on the right. The interactive media program at Mound City provides introductions to the other sites in the region, including those not open to the public.

Outside, walk among the 23 mounds and their low enclosing wall; each covers the remains of a funerary building. Some held spectacular collections such as effigy smoking pipes or shimmering blankets of mica. This place is unique among surviving Hopewell era sites, and may reflect a period of time when mound building was beginning to be augmented by bigger, grander ideas about geometric form and embracing enclosure. Here the people created a collective cultural monument on a much larger scale, a possible prototype for the more precise and complex geometric figures to come.

Play video

The first Euro-American pioneers named the site “Mound City.” Squier and Davis investigated in detail in the 1840’s.

SITE HISTORY

SITE HISTORY

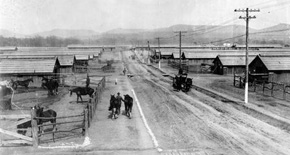

Mound City was first granted to a white owner in 1798; and in less than 40 years the busy Ohio and Erie Canal passed nearby. When Squier and Davis surveyed the site in 1846, the forest still preserved most of the mounds. But soon the land was cleared for farming. Plows passed right over the walls, and most of the mounds, year after year. In 1917, the land was bought by the Federal Government for Camp Sherman, a World War I training camp. The army was shaving off all the mounds to build barracks when Henry Shetrone of the Ohio Historical Society stepped in and asked that the central mound be spared. In 1923, the site became a National Monument, and three years later the Ohio Historical Society restored the mounds. Since 1992, Mound City has been the center of the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park.

Play video

The huge Camp Sherman covered Mound City and much of the surrouding land in the early 20th century.

AN ANCIENT NECROPOLIS

AN ANCIENT NECROPOLIS

To its builders, this elaborate necropolis must have been a place of reverent memory, like Britain’s Westminster Abbey, or the memorials along the Mall in Washington, D.C. All these mounds cover the floors and post holes of ceremonial buildings. The patterns show a variety of designs, though most often a rectangle with rounded corners.

Inside, fires burned in shallow clay basins. The ceremonies included the cremation of the dead, and objects were ritually killed (broken or burned) to be left with them. The ash and remains were swept up, and placed carefully on the building floor, or on low earthen platforms. In a final ceremony, each building was taken down or burned, and a mound was built over its remains and contents. While Mound City was in use, visitors would have seen functioning buildings here, and also those already memorialized under mounds.

BUILDINGS

BUILDINGS

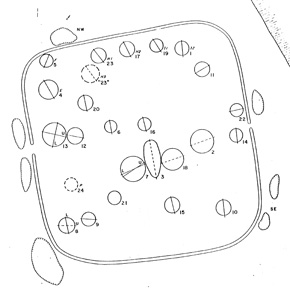

Discoveries under the walls suggest that people lived and held rituals here well before most of these mounds were built. During the first century A. D., a few ceremonial houses were put up; their fire-basins and doorways had a variety of orientations. Some of these were probably mounded over by the time the second phase began, at the start of the second century. Three central buildings were erected, creating a new ritual focus. At least seven other buildings were built, pointing towards this focus. And the low wall was added to enclose things, strengthening the formality of the site, and its sense of common purpose. It resembles the shape of an individual building; and its two gates define an axis. This centralization and enclosure of the whole site may reflect an increasing organization and social ranking among the people. By the early third century, mounding was complete.

Plan of Mound City showing the orientation of the sub-mound structures, and the dominance of the central features.

CENTRAL MOUND

CENTRAL MOUND

The Central Mound was the tallest one here – 19 feet when first measured in the 1840s. The building beneath was complex. A sunken room was entered along a ramp. When this room was no longer used, the builders left behind only a shallow basin, its clay lining baked red by many fires. Some time later, leaving a set of posts in place, they filled the room, and built a new clay fire basin exactly above the old one. Upon a new floor, of puddled clay and sand, they erected a building, and laid out ten cremated burials on log-supported earthen platforms, roofed with bark.

Three elaborate burials in the Central Mound were probably respected leaders or elders. The objects left with them probably meant many things, including a person’s special work in life, their status, and their connections to the community and to powerful forces in nature. The amanita mushroom, known for its poisonous and hallucinogenic qualities, is represented as a copper effigy, and may suggest how a priest could make a dream journey to commune with the spirits of the dead.

PIPES MOUND

PIPES MOUND

Under another mound, a large bag (placed next to a clay basin) was filled with ashes, beads, some copper items, and about 200 carved effigy pipes, all purposely broken. The pipe bowls portray a variety of animals, carved with accuracy and great artistry. Several showed human heads. Another deposit of almost identical pipes was found at Tremper Mound, 40 miles south of Mound City along the Scioto River.

The animals shown on the Mound City pipes are traditional figures in Eastern Woodland stories, creatures with their own will and power. Lenape storyteller Annette Ketchum:

The story I want to tell you is about why the turtle is so important to the Lenape people. And that’s because, a long time ago, they lived by the ocean, by the big water. And one day, the water started to rise. And it was a large, large flood, it came higher and higher, pretty soon the people were just up to their neck, they just believed they were going to drown for sure. And they didn’t know what to do. And they cried to the Creator. And about that time, a large turtle came up out of the ocean; he says, ‘Get on my back, and I will save you.’ So all the people got on the turtle’s And they cried to the Creator. And about that time, a large turtle came up out of the ocean; he says, ‘Get on my back, and I will save you.’ So all the people got on the turtle’s back. And they swam around until the water went down, and then came back up to the shore and let them off. And they said, “Oh, thank you, Turtle. From now on, we will call ourselves Turtle people. And we will be known as the Turtle clan. And to this day, we are still known as the Turtle Clan. And I’m Turtle Clan, so I especially like that story.

Play video

Play video

Gerard Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa) tells of a tradition that may explain why the pipes at Mound City and Tremper Mound were broken deliberately.

PAIRED MOUNDS

PAIRED MOUNDS

Near the western gateway stood two mounds, unusually close together. Two buildings once stood here: an older one, and a newer, smaller one, connected by a gallery. There were several pits and clay basins inside, suggesting it may have been the place of preparation for the more formal rituals and deposits next door. The larger building held elaborate burials. On one low platform, four people were laid to rest in what William Mills called “a splendor of mica,” along with many precious objects. Four other platform burials were similarly marked by precious objects, now in the Visitors Center: double-headed vulture plates, an unusual copper animal headdress with movable ears, copper deer antlers, and a mica human torso – perhaps the paraphernalia of ritual performances, mythic re-enactments. This “double building” may have been a model for other larger versions at the Seip and Liberty earthworks.

ACTIVITIES AND AGRICULTURE

ACTIVITIES AND AGRICULTURE

In its day, Mound City was much more than just a silent “necropolis” or “city of the dead.” There was a lot going on here, including various building projects right up until the final, enclosing wall was built. And maybe a lot of parties and festivals: the lowest layers of soil deposited in the wall contain large amounts of charcoal and deer bone. Site archaeologist Bret Ruby:

It was a much more active place; it was used for a whole variety of functions including feasting. Another point this shows about Mound City is that the embankment wall was probably one of the last things constructed. What you see out there today is its final form, essentially after its abandonment. So it’s important to think of this as a place that grew over time – maybe as much as four centuries, which is an incredibly long time span, many generations.

Hopewell society benefited from the fertility of the region’s ecosystems, but also practiced a well-developed agriculture. Archaeologist Ruby explains:

Hopewell people were farmers, they were participating in the transition between a hunting and gathering lifestyle into a farming lifestyle, including the domestication of starchy, oily plants. They were clearing ground, planting and harvesting crops – fully committed agriculturists. There would have been significant openings in the forest, caused by clearing ground for agriculture. They’re moving, clearing plots, using them for a period of years, and then clearing other plots. So it’s a shifting movement across the landscape. New plots are being opened, old plots abandoned and reclaimed by nature.

Play video

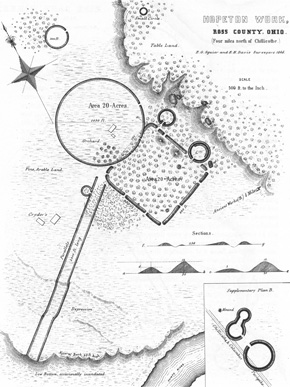

The Hopeton Earthworks, just across the river from Mound City, can be visited as part of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

SQUARES WITH ROUNDED CORNERS

SQUARES WITH ROUNDED CORNERS

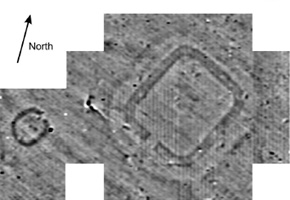

Mound City’s overall shape is a square with rounded corners resembling the houses under its mounds. Until recently it seemed unique among earthworks. But archaeologist Jarrod Burks has discovered several now-invisible earthworks that were drawn as circles by nineteenth century explorers, but have been proven by modern remote sensing to be squares with rounded corners:

Perhaps all these old maps, say, Squier and Davis or the other publications that show a circle: it seems that a significant number of these circles aren’t circles, they’re actually squares with rounded corners. That’s significant because especially Mound City seems to appear out of nowhere, when in fact that’s not true: there seems to be a lot of other earthworks with these shapes, these squares with rounded corners.

A section of Dr. Jarrod Burks’ new data from the Junction Group near Chillicothe, with its “squircle” (square with rounded corners) shaped earthwork.

THE SHRIVER CIRCLE

THE SHRIVER CIRCLE

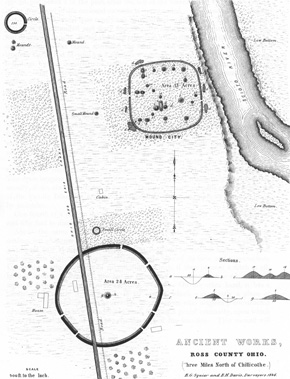

Squier and Davis’s map of Mound City also shows a huge circle, just to the south. Its remnants lie in the fields along Route 104. Now much degraded, its ghostly remnants are still visible in old aerial photos. When the highway was widened recently, archaeologists investigated: The exterior ditch was originally twelve feet deep, and carefully lined with a foot-thick layer of clay – to hold the slopes, and water. Associated burials in the central mound suggest this monumental work was here before Mound City itself.

It’s probable that Shriver (circle) and Mound City (square) became prototypes for a new hybrid design at the Hopeton Earthworks (just across the river), and in turn led to all the geometrical experimentation and perfection found in the Paint Valley and at Newark and elsewhere throughout the Hopewell era.

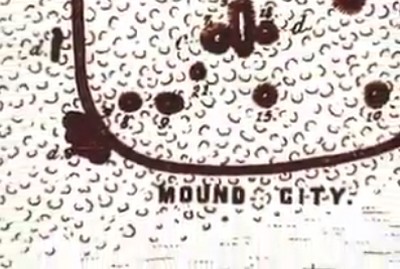

Squier and Davis’s drawing of Mound City and the huge Shriver Circle in 1848, also showing the canal and the future Route 104.

HIGH BANK EARTHWORK

HIGH BANK EARTHWORK

Hopeton and High Bank are two major geometric earthworks that remain (though degraded) in the immediate Chillicothe area, now under the protection of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. Hopeton is now open to visitors, while High Bank remains a research preserve.

The linked circle and octagon at High Bank look remarkably similar to another pair at Newark, Ohio. Archaeologists are still investigating, but it seems the shapes are similarly connected to astronomical events. The crossaxis of the octagon points to the northernmost rising of the moon. And one of the octagon walls points to the summer solstice sunrise. Between them, these two alignments determine the orientation, and the shape, of the octagon. More mysterious are the walls and circles that trail off to the southwest.

While Newark and High Bank are about 70 miles apart, they were designed using similar principles. Their circles share the same diameter, and each harmonizes with its octagon: at High Bank, points at the center of all eight sides of the octagon can be joined to form a circle of equal diameter. Ray Hively and Robert Horn have shown that High Bank, like Newark, encodes all eight lunar standstills, plus the four solstices, while the axes of the two designs are exactly 90 degrees apart. The builders could not simply replicate Newark’s design, due to the difference in latitude, so had to create here another equally complex and subtle instrument.

High Bank Earthworks centers on an axial line that also connects two other giant earthworks over a distance of several miles.

HOPETON EARTHWORK

HOPETON EARTHWORK

Directly across the Scioto River from Mound City are the Hopeton earthworks: a large square, with a circle slightly overlapping it. Two smaller circles mark gateways to the square in different ways; and long parallel walls lead to the bank of an old channel of the river. The ancient walls once stood twelve feet high, but farmers have plowed, and even bulldozed them, so only faint traces remain. Yet on old aerial photographs, or with new magnetic sensors, the ancient lines still leap to life.

Dr. Mark Lynott explains his discoveries inside the wall at Hopeton, during the summer of 2002:

We’re near the center of the wall here, and this shows very clearly a section of how the wall is constructed. At the base we have a yellow subsoil where the topsoil had been stripped off. And then the Hopewell came in and put this black section of sterile clay in here. It has a little bit of burned material but no artifacts. And then above it they’ve added this red, somewhat loamier, clay; and this is highly magnetic, and that’s what’s worked so well with our magnetometers.

Dr. Lynott continues:

This is, in its own way, by the organization of the Hopewell people, as spectacular as the Mayan Pyramids, as the Egyptian Pyramids, because these folks are not agricultural societies; they’re not organized that way. They’re much more of an egalitarian group of people; they’re much more mobile, and yet they still managed to build some spectacular earthen monuments here. And what’s incredible is that doesn’t fit with the traditional anthropological models of social organization and accomplishments.

After the 1930s, mechanized agriculture rapidly accelerated the destruction of many of the giant geometric earthworks like Hopeton. We can trace this process by comparing aerial photographs: In 1938, the walls still showed up clearly, even the long parallels going down toward the river. But by 1985, though, nothing is visible. The walls have been flattened to low, wide shapes, and are barely visible at all, from either the air or eye-level.

Play video

Miami Tribe official Julie Olds talks about why preservation of sites like this is important to Native people.

An aerial photo from 1938 shows the clear outlines of Hopeton’s circle andsquare, similar in size to Shriver Circle and Mound City, respectively.