Chillicothe

ABOUT THE ROUTE

ABOUT THE ROUTE

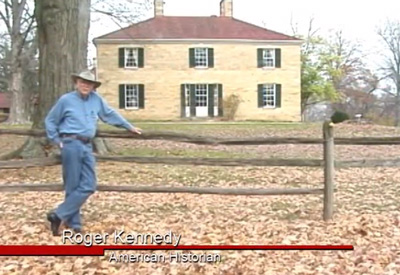

Historian Roger Kennedy has aptly called Ohio’s first capital the “Delphi of North America” no less for its remarkable concentration of Greek Revival architecture than for its status as the core area of the brilliant Hopewell culture, whose influence was spread across much of the continent seventeen centuries ago [see: Mound City]. The downtown historic district includes restored bed-and-breakfasts from which to plan several days’ excursions here in the “heartland of ancient America.”

The Ross County Convention and Visitors Bureau, with their website (at: http://www.visitchillicotheohio.com), or downtown offices, can provide further information on where to stay and eat, and what to do in the area.

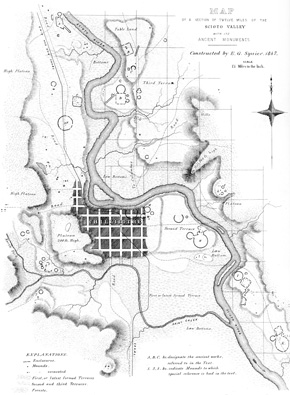

This plate from Squier Davis's book shows the dense concentration of ancient geometric earthworks in the vicinity.

HISTORIC DOWNTOWN

HISTORIC DOWNTOWN

Arriving in Chillicothe by US Route 50 (from Bainbridge), brings you directly into downtown on Main Street. Its intersection with Paint Street marks the center of 16+ blocks of remarkable historic architecture, much dating from the time when Chillicothe newspaper editor Ephraim Squier and physician Edwin Davis collaborated on their Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, the first publication of the new Smithsonian Institution in 1848.

The name “Chillicothe” means “principal town” in Shawnee, and old Ohio maps show several Shawnee-era “chillicothes.” But it was this one that, long before, was the center of Ohio’s earthwork building culture, and that in 1803 became Ohio’s first state capital. Prosperity came early to this village on the banks of the Scioto, a gateway to the large “Virginia Military District” between here and the Little Miami River to the west. Early culture and commerce were influenced by wealthy Virginia land-owners, whose huge estates produced cattle, pigs, and corn in abundance.

Today, historic districts preserve some of America’s best nineteenth-century commercial urban fabric, especiallly along Paint, Second Streets, and Water Streets.Superb specimens of historic house styles, churches, and public buildings line the nearby streets. Especially impressive are the many Greek Revival examples, dating from the grand days of the canal era: the 1830s through 50s.

Play video

The most exquisitely detailed Greek Revival examples are near Fifth and Paint Streets and along West Second Street.

EARLY COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS

EARLY COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS

In 1831, the new Ohio and Erie Canal came to Chillicothe, creating decades of prosperity as a commercial hub for the great agricultural lands to the west. Local historian Kevin Coleman explains the result:

It’s very much a quintessential American town. I like to call it the Williamsburg of the West, because Williamsburg in Virginia has been restored to its colonial condition; so it represents America at the time of the American Revolution. But Chillicothe here, beyond the Appalachian Mountains in the New West, represents America very much in the 19th century. We have a lot of antebellum, pre-Civil War commercial buildings that survived. It’s probably because of a disastrous fire in 1852: the town rebuilt quickly afterwards but it slowed down the economy, so those buildings weren’t replaced later on. So in a lot of towns where you have high Victorian buildings, we have pre-Civil War buildings still standing.

Quaint old storefronts line Water Street, once the canal route. James Emmitt’s giant, canal-side warehouse (1850s) still stands on Mulberry Street. Paint Street presents a whole “museum” of both early- and late- 19th century commercial architecture, plus the unusual 1850’s courthouse.

ROSS COUNTY HERITAGE CENTER

ROSS COUNTY HERITAGE CENTER

At Fifth and Paint Streets in Chillicothe is the newly arranged Ross County Heritage Center, which unifies the county Historical Society Museum and the McKell Library. Both are valuable for learning more about ancient earthwork-building cultures and the local history of the Chillicothe area.

A collection of historical structures house the Ross County Heritage Center, presenting the way of life of early settlers, along with some ancient objects found here.

THE STORY MOUND

THE STORY MOUND

About halfway between downtown Chillicothe and the Adena Estate stands the Story Mound, preserved by the Ohio Historical Society near the corner of Allen and Delano Avenues. It closely resembles in size and shape the now-lost Adena Mound: originally 25 feet high and 95 feet in diameter. From the same period, it probably matches its more famous former neighbor in function as well: Excavations at the Adena Mound in 1897 [see: Adena] uncovered the burial of a young man, plus a set of postmolds, forming a ring. This pattern was the first evidence of the round structures, built to enclose funeral rituals, that lie under Adena mounds. This building (or fence) was about fifteen feet across, and was ritually dismantled or burned after its use, and buried under the mound.

BELLEVIEW AVENUE

BELLEVIEW AVENUE

From the corner of Fifth and Walnut, Belleview Avenue angles up the hill to the southwest. Once a piece of Zane’s Trace, on its way from Wheeling (now in West Virginia) to Maysville, Kentucky (then called “Limestone”), it passes mansions like the idyllic,1826 “Tanglewood” with its exquisite Greek Revival portico. Belleview leads to the entrance to Grandview Cemetery, where Renick, Worthington, and other prominent founders are buried; and from which there are fine views of the town, the nearby Great Seal Range, and the huge valley of the Scioto.

Grandview Cemetery affords views of Chillicothe and the Great Seal Range, a prominent geographic focus since antiquity.

THE TEAYS VALLEY

THE TEAYS VALLEY

The wide river valleys south of Chillicothe, and also around Cincinnati, are part of an ancient, pre-glacial river system. These huge rivers flowed northward out of West Virginia and Kentucky, before turning west and entering the Mississippi basin. The biggest traces are here at Chillicothe, and south of here at Piketon. Historian Kevin Coleman explains:

The Teays River was the mother of all rivers in this area. It was actually the head waters of the Mississippi, but it bent around though Illinois and Indiana and Ohio, and its head waters were in western North Carolina. It actually flowed through the Appalachian Mountains because when it started, the mountains, at least the second version, which we have today, had not been formed yet. The New River Gorge is the head waters of the Teays, but because of three or four glacier advances, the whole area in Ohio, and a little farther south, has been completely re-plumbed. So where the Teays created what is now the Scioto Valley, and it flowed northward, now we have the Scioto, which is a smaller river flowing southward.

These ancient rivers left behind superb, wide, flat, well-drained terraces, that stand safely above the newer, smaller rivers. They became perfect building sites for the giant geometric earthworks, two millennia ago.

TECUMSEH

TECUMSEH

The story of the Shawnee leader Tecumseh is retold in an outdoor drama every summer near Chillicothe. “Tecumseh” in Shawnee means “shooting star” – suggesting the spectacular but brief career of this legendary Indian leader. Born in 1768 near present-day Piqua, Ohio, he gained a reputation for bravery and leadership in battles against the U.S. army in southern Ohio.

After their defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, most other Indian leaders thought their only path to peace was to sign the Treaty of Greenville, giving up their southern Ohio lands. But Tecumseh refused. With his brother Tenskwatawa, called “The Prophet,” he worked heroically in the early 1800s to persuade all the tribes in the region to unite and push the white settlers back across the Appalachian Mountains.

Troops led by William Henry Harrison destroyed Tecumseh’s base at Prophetstown, Indiana, and with it his dream of a united Indian resistance. Tecumseh joined English forces in the War of 1812, still trying to turn back the tide of settlement, but was killed in battle.

The Shawnee hero Tecumseh, like Thomas Worthington, initially hoped for peaceful co-existence between the races. Tecumseh is the subject of an outdoor drama near Chillicothe each summer.

ADENA ESTATE

ADENA ESTATE

On the advice of his friend and political mentor Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Worthington engaged the services of America’s first professional architect, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, to prepare the plans for his new house, in his adopted homeland of the Scioto Valley. Constructed from 1802-07, it would become the focal point of the huge estate.

To reach Adena, follow the signs off of State Route 104 just north of Chillicothe (on the way to Mound City). The mansion and gardens are beautifully restored, with period finishes and furnishings, and a large new museum and education center interprets the life and history of early 1800s Ohio (847 Adena Road, Chillicothe, OH 45601, (740) 772-1500).

Adena’s kitchen is part of a detailed tour illustrating 19th century life on an early Ohio estate.

A PALLADIAN MANSION

A PALLADIAN MANSION

The design of the house drew on influences from many sources, thanks to Latrobe’s extensive travels and education: West Virginia stone manor houses like the one Worthington grew up in; works of the Italian Renaissance master Andrea Palladio (Jefferson’s favorite); and distinguished British and French models. The innovative layout increased the grandeur and elegance of the “center hall,” provided an overlooking balcony, refined the traffic flow among the bedrooms, and introduced Jeffersonian inventions like a revolving serving shelf. The classical idealism and innovation in the design have earned it the title, “Monticello of the West.”

Worthington named his new house “Mount Prospect Hall” and only later in 1811 did he discover the term “Adena” and rename his estate. The mansion remained in the Worthington family until 1898, and, once acquired by the Ohio Historical Society in 1946, was restored, along with several of the out-buildings, and most recently, the gardens and orchards.

The Adena Mansion’s Palladian plan is beautifully constructed in local Waverly sandstone.

THOMAS WORTHINGTON

THOMAS WORTHINGTON

Thomas Worthington was born into a well-to-do family in Charlestown, now in West Virginia, in 1773. Attracted by abundant farmland and new social and political opportunities in “the West”, he moved to the Scioto Valley in 1798, with his new wife, and their friends and relatives. He soon became a leading citizen in the new village of Chillicothe, and one of the early advocates for Ohio statehood, both locally and in Washington. He was a key author of the Ohio Constitution, one of the new state’s first senators, and its sixth governor.

Later he was elected to the state legislature, where he strongly advocated building the canal system.

The lands of his beloved “Adena” grew to twenty-five-thousand acres, and produced cattle, pigs, and fine Merino sheep, as well as a diversified mix of crops. His idealism for what the new lands in “the West” could become is reflected in his ambitious choice to model his estate on the most distinguished European classical models, and to hire America’s leading architect to draw the plans.

COFFEE CUPS AND CAKES

COFFEE CUPS AND CAKES

In the Drawing Room at Adena, just after it was completed, Worthington held a meeting with Tecumseh and other Indian leaders. It was an effort to secure peace and respect between the races; and much was at stake. Historian Roger Kennedy tells the story:

All the ironies of the relationship between the founders and the Indians came together in this room in 1807. Equals were dealing with equals, and in fact, so conscious of their equalness that the Indians made jokes about the coffee being distributed to them, pretending that they were savages, which they were not. They in fact spent a whole week around here, living with the Worthingtons, and celebrating their common presence in the midst of a deep antiquity – to which the Worthingtons were visitors, and the Indians were not.

IDEALS OF RESPECT

IDEALS OF RESPECT

For his interests in Ohio antiquity, and enlightened race relations, Worthington was unusual among his former Virginia compatriots. Roger Kennedy continues:

He was a truly remarkable man. Not only did he set his slaves free as he came across the Ohio River, but he lived all his life in a respectful relationship with the Native Americans who were living here, and who had built those great earthworks. He had a strong sense from the outset that he was a newcomer in a very ancient land. He was not only interested in politics, he was interested in antiquity and architecture as well.

Worthington’s friend Albert Gallatin, whose glass-factory in Pennsylvania supplied the windows for Adena, also had high respect for Native America:

Like Worthington, Gallatin was an abolitionist and devoted to a respectful relationship to the Native Americans of their own time, and of the memory of the achievements of Native Americans of American antiquity. Gallatin spent the next forty years after this house was created founding and providing to the Bureau of Ethnology, which became the Smithsonian Institution.

The first publication of Gallatin’s new “Smithsonian” was by two men from right here in Chillicothe, Ephraim Squier and Edwin H. Davis, and was filled with Ohio’s spectacular antiquities.

THE DELPHI OF NORTH AMERICA

THE DELPHI OF NORTH AMERICA

The State of Ohio’s Great Seal was famously invented here at Adena, where a view from the grounds opens onto a wide panorama of the Scioto Valley. That range of hills is now the “Great Seal State Park”. Roger Kennedy talks about the significance of this landscape:

One fine morning after a night spent playing cards, Thomas Worthington and a young painter were looking around for the place to immortalize for the Great Seal of Ohio. And when they came to this place they said essentially, “it’s a take.”

The sun rises over Karnak, and Stonehenge, and Delphi; and this is the Delphi of America, a place surrounded by an immense array of ancient architecture, telling us that people have been doing their best to make great work around here for at least a couple of thousand years.

The “Delphi” comparison suggests that, like the Greek site of that name, this was a place the whole civilization understood as the center of their sacred world, and a natural goal of pilgrimage.

THE ADENA MOUND

THE ADENA MOUND

When Worthington established his estate here, a 27-foot mound, inside an earth ring, stood at the foot of the hill. Finds from this mound are the reason archaeologists applied the name “Adena” to the culture which thrived in this region from about 1000 BC to AD 100. The excavations destroyed the mound; its location now lies beneath the streets and houses near the small Lake Ellensmere.

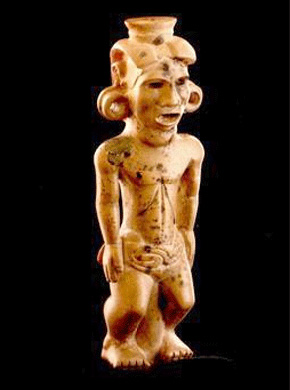

Mills’ excavations revealed this spectacular pottery pipe with the main burial: an eight-inch figure of a man wears a loincloth and feather bustle, his knees are bent as if he’s dancing. Retired Ohio Historical Society Curator Martha Otto:

This pipe is unique in that we’ve never found another one like it, carved in this form of a human – a full figured man standing with his hands at his sides, and so forth. And over the years that particular pipe, which we call the Adena Pipe, named after the site, has become kind of emblematic of the Historical Society, and of the Adena culture.

The Mound itself was typical of Adena architecture: the free-standing conical mounds, sometimes with surrounding rings and ditches, that are found throughout Ohio. Martha Otto continues:

You do get situations like in Athens County, around the Plains, where there was quite a grouping of conical mounds; the same around Charleston, West Virginia. But I think by and large, if a mound is located that it is separate from any other, usually we classify it as Adena.

The most spectacular of the Adena mounds are at Miamisburg, Ohio, and Moundsville, West Virginia, and the beautiful Conus Mound at Marietta, with its well preserved surrounding ring.

The Adena Pipe has become one of the most iconic objects in the collections of the Ohio Historical Society in Columbus.